Hunters of the Lost City, a story twenty years in the making

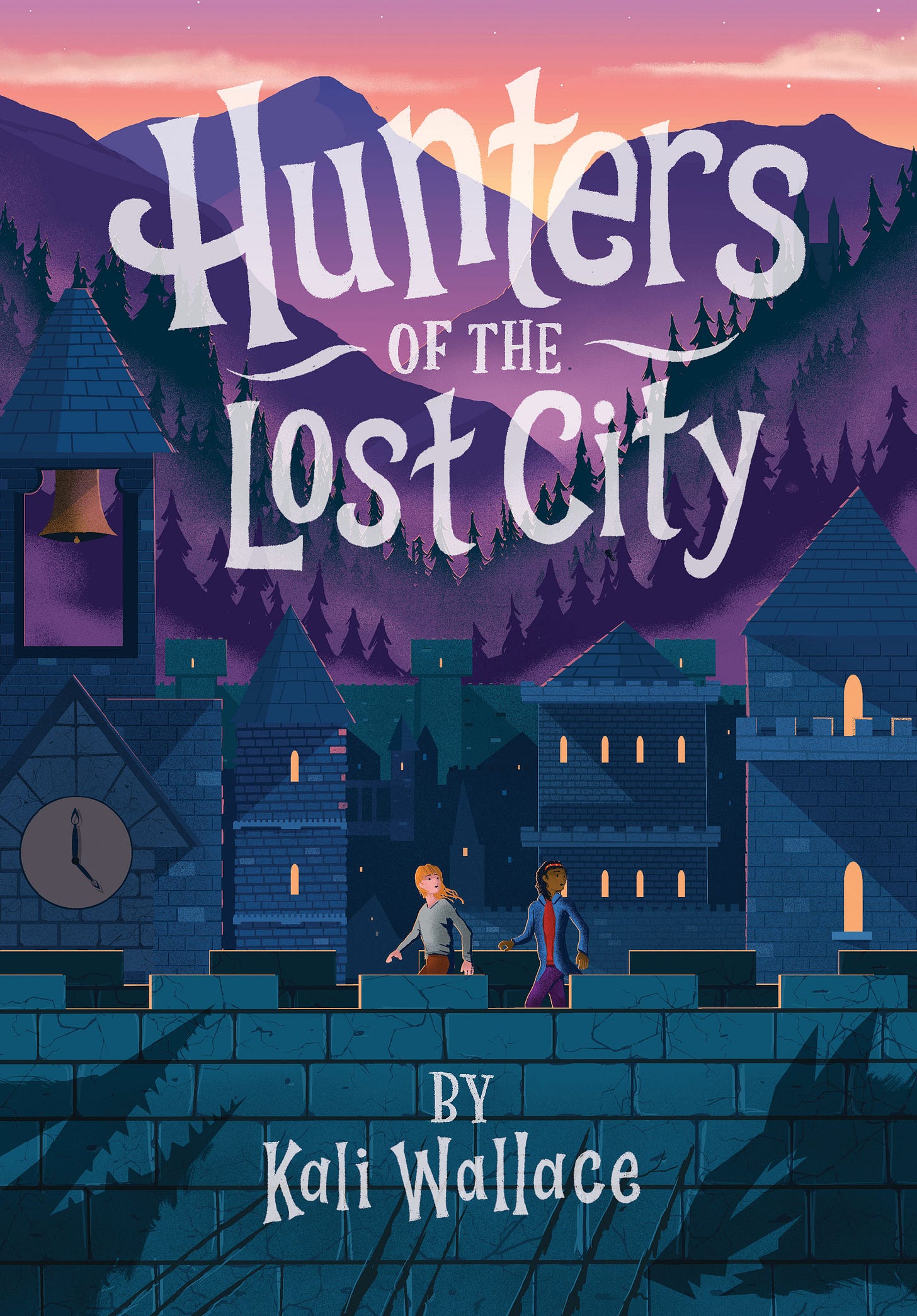

I am delighted to reveal the cover for my next novel, Hunters of the Lost City, which will be published by Quirk Books on April 26, 2022. It was a great deal of fun to write another fantasy book for middle grade readers (and everybody else!), and I can't wait for you to meet Octavia and explore her strange, magical world. I talked about the book and the cover (which I love beyond all reason) over on the Quirk blog, and I've included some preorder links below.

Here's what it's about:

Packed with shocking twists, frightening monsters, and dark magic, this is a page-turning fantasy adventure for middle-grade fans of Holly Black and Tamora Pierce.

Twelve-year-old Octavia grew up believing the town of Vittoria was the only one left in the world. The sole survivors of a deadly magical war and plague, the people of Vittoria know there’s no one alive outside the town walls—except the terrible monsters that prowl the forest.

But then the impossible happens: Octavia meets another girl beyond the walls, someone who claims to have traveled from far away. Everything she’s ever believed is thrown into question, and there’s no going back.

In her quest for the truth, Octavia discovers a world full of lies, monsters, and magic. She’ll have to use every scrap of her wits and courage to uncover what’s real about her family, her home, and the rest of the world.

And here are some places where you can preorder it:

QUIRK - INDIEBOUND - ANNIE BLOOM’S (PORTLAND)

MYSTERIOUS GALAXY (SAN DIEGO) - TATTERED COVER (DENVER)

BARNES & NOBLE - AMAZON

Like a lot of my stories, Hunters of the Lost City has a long and patchy history. I started writing it more than twenty years ago. In November of 2000, to be exact, which I know because I never delete anything and that's when the first words were written in the original file. I was in my senior year at Brown University. Although I have been writing fiction for as long as I can remember, I didn't write a lot of fiction in college. This was partly because I was too busy, but it was also because I had internalized the idea that it was a waste of time if I wasn't aiming to do something with it, and I was never aiming to do anything with it because I didn't think it was any good.

I did take a couple of creative writing classes at Brown, and I enjoyed them and learned a lot, but I always carried into them the thought that it didn't mean anything, I wasn't going to do anything with my writing, I just wanted an easy credit and an excuse to write. And, well, that was true. They were easy classes. And they were a good excuse to write. I never let myself think of them as more than that. It was always a bit awkward to be in those workshops surrounded by creative writing and English lit students. I used to do my physics homework (electricity & magnetism, specifically) during the mid-class break of an advanced fiction writing workshop, and I remember a fellow student laughing about how it looked incomprehensible to him, while at the same time I was thinking—well, I was almost certainly quietly panicking because I needed to finish my problem set and I kept getting Maxwell's equations mixed up and I was very overworked that semester, but I was also thinking that the way he and the other writing students talked so comfortably about stories was equally incomprehensible to me.

I don’t remember if I was taking a creative writing class during November of 2000. I might have been. But when I started writing the story that would eventually evolve into Hunters of the Lost City, I probably didn't have any goal in mind except to create a bit of escapism for myself.

In those earliest versions, the story isn't much more than a few description-heavy scenes: a girl stalking monsters through a winter orchard at dusk, looking down on the lights a walled town in a remote valley, and returning to the safety and warmth of the town while knowing dangers still lurked outside. I never finished it; I didn't know what to do with it.

Like everything I wrote in those days, it was heavy on adjectives and atmosphere but rather light on anything resembling character or plot. That was how I wrote for a long time. I was good at sentences, good at setting a scene, good at being a bit clever, and I tried to convince myself that was enough. It never was enough, but I had internalized another faulty lesson about writing: the belief that competence and cleverness are all that a story needs.

That one is a tough belief to shake, much harder than the notion that art only matters if it has a monetary or commercial value. It's very easy to convince ourselves, as we write, that our goal is to prove that we are smarter than our readers. Many of the ways we talk about and teach writing reinforce the idea that competence and cleverness are the keys to a successful story, even if we aren't doing it on purpose. We talk about what a story is trying to do, as though each bit of prose is a serial killer whose internal fantasies have to be discerned from outward clues. We talk about what the story is really saying, as though it's natural to expect every story to be written in code, to expect every truth to be obscured, to expect every author to be sitting behind the curtain with a smug look and a secret codex. It's easy to come out of such conversations thinking that obfuscation is more valuable than clarity, that writing around a story requires more skill than telling a story, that inscrutability of language is equivalent to complexity of thought.

Every few years, for two decades, I took out that unfinished, unformed idea and poked at it, sometimes changing the point of view, or the age of the main character, or the world-building and background. But I never expanded or developed it. It never grew longer than a couple thousand words. The core images always remained the same. A walled town high in the mountains. Orchard terraces. The beginning of winter. A girl on the hunt.

It was pure coincidence that I happened to be going through one of those rare instances of playing around with that old idea when Alex Arnold reached out to ask if I wanted to write another middle grade fantasy novel. I had very much enjoyed working with Alex on City of Islands, and I was excited to work with her again in her new position at Quirk Books. So I promptly said, yes, of course, middle grade fantasy, got it, right away—then realized I did, in fact, have the perfect story premise just sitting around and waiting.

A lot of authors hate writing synopses or pitches, because it's never easy to distill an entire novel down into a couple of rather bland pages, and this can be especially difficult when you haven't written the story yet and have only the vaguest idea of how it's going to unfold. I kind of hate it too, but I've realized recently that I also kind of like it. I like that it forces me to think about the structure and progression of the story in a way that won’t let me hide behind the atmosphere and description, the fancy window-dressing and frills, the stuff that’s easy for me. I'm very good at using nice words to distract from a flimsy story—so good that I am always my own first and most gullible mark.

When I sat down to expand my old, old idea into a pitch for a proper novel, I had to stop thinking of it as a series of images—however appealing those images might be, to hang around in my head for twenty years—and start digging into the guts. Who is that girl in the orchard? Why is she out there alone? Why are there monsters that need to be hunted? Why is it that this walled town is so alone and isolated? Why should anyone care about any of this?

All the pieces were there. They had been there all along. But the story had no beating heart, not until I forced myself to stitch all those pieces together and give them a proper lightning shock to bring it alive. It worked, this time. Hunters of the Lost City is a good book. It has monsters and magic and brave girls and dangerous adults and a lot of snow. I enjoyed writing it. I hope you enjoy reading it.